Breaking the Pot

How it came to be…

The Norwegian Embassy approached Nanzikambe in 2004. The year after next was to be the Ibsen Centenary. Would we be able to adapt an Ibsen play for Malawi? Not yet another dry European story for the African community to swallow, I thought. Why cant we be funded to tell African stories, stories of urgent and real importance to the Malawian audience?

The Norwegian Embassy approached Nanzikambe in 2004. The year after next was to be the Ibsen Centenary. Would we be able to adapt an Ibsen play for Malawi? Not yet another dry European story for the African community to swallow, I thought. Why cant we be funded to tell African stories, stories of urgent and real importance to the Malawian audience?

After these initial indignant, and perhaps ungrateful thoughts, I came to realise the fantastic possibilities within this proposition, and began, through discussion with our colleagues at the Embassy, to shape the scope of the project. The task we set ourselves was to undertake a reinvention of an Ibsen play for the African context. We embarked upon what was to be an extensive and riveting journey in to the world of Henrik Ibsen, and in to love and marriage in the Malawian home. Very quickly, my fellow artists at Nanzikambe and I were hooked.

To help us choose which play would be the most appropriate for Malawi, and for us to become better acquainted with the ‘father of modern drama’ we were funded to go on a research mission to Norway – to attend the Ibsen Festival at The National Theatre in Oslo. Here my close colleague Muthi Nhlema, and I saw countless productions – most in either Norwegian or German. The Malawian and the English girl became a little dazed.

To help us choose which play would be the most appropriate for Malawi, and for us to become better acquainted with the ‘father of modern drama’ we were funded to go on a research mission to Norway – to attend the Ibsen Festival at The National Theatre in Oslo. Here my close colleague Muthi Nhlema, and I saw countless productions – most in either Norwegian or German. The Malawian and the English girl became a little dazed.

It was through our discussions about the issues that are most pertinent to Malawian society that we found our way towards a decision. Ibsen writes about what he sees as being the ills beneath his society – power, greed, inequality, bigotry, corruption. His plays often attack entrenched beliefs and assumptions. It became clear that many of Ibsen’s plays could be made applicable to Malawi.

We asked ourselves many questions during this process of choosing the play – the most pertinent being: in our own experience of life, here and now in Malawi, where is the greatest and most pervasive injustice?

In the end, the decision came from personal and strong sentiments expressed to me by Malawian friends and colleagues. The stories of consistent subordination of women within their families and the expressions of fear about the expectations placed by society upon men led us closer towards A Doll’s House. It was clear that there was a growing discomfort amongst this particular group of artists at the cultural and social status quo. In all our discussions there was a strong underlying need to express a cry for a transformation in the relationship between men and women. We also felt strongly that after productions that provided fierce political debate by looking at the relationship between leaders and the people: Playing with Food, African Macbeth – it was time to look at more personal relationships, at love and marriage.

Ibsen’s A Doll’s House portrays a couple trapped by the expectations that society places upon them. These expectations include the preconditioned gender roles that men and women must conform to, and fulfill. The story depicts a woman questioning her duty to her husband and seeking to escape the oppressive confines of her marriage. In so doing, it examines, in a profoundly meaningful and complex way, the social fabric that nourishes destructive gender stereotypes.

Ibsen’s A Doll’s House portrays a couple trapped by the expectations that society places upon them. These expectations include the preconditioned gender roles that men and women must conform to, and fulfill. The story depicts a woman questioning her duty to her husband and seeking to escape the oppressive confines of her marriage. In so doing, it examines, in a profoundly meaningful and complex way, the social fabric that nourishes destructive gender stereotypes.

We were decided. A Doll’s House was to provide for us the perfect mechanism for placing love and marriage in Malawi under scrutiny.

To make the adaptation process richer, to provide insight in to the original Norwegian text and to deepen our artistic link between Norway and Malawi, we decided to approach Norwegian writers to see if they would be interested in collaboration. We were recommended a certain Karl Hoff, who has both a great interest in Ibsen, and experience working on theatre projects in different African settings.

To make the adaptation process richer, to provide insight in to the original Norwegian text and to deepen our artistic link between Norway and Malawi, we decided to approach Norwegian writers to see if they would be interested in collaboration. We were recommended a certain Karl Hoff, who has both a great interest in Ibsen, and experience working on theatre projects in different African settings.

Karl’s role was to take care of Henrik Ibsen’s original intentions and meaning during our journey in to the Malawian context. But he has brought much more to the process. Karl’s openness, compassion, incisive and conscientious attention to detail, and passion for truth and justice has been of unquantifiable value.

In these early stages, we also conceived the wider scope of the project to include a longer and more detailed adaptation process, an accompanying documentary, performance training for local artists, publishing the adapted text and extending our audience by touring to places that have never received national theatre groups before.

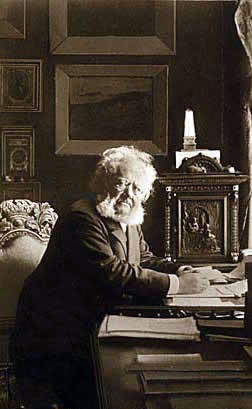

Henrik Ibsen

Born 1828, in Skien, Southern Norway, Henrik Ibsen was the son of a successful businessman. When he was a boy his family’s fortune took a dramatic turn for the worse. They experienced a severe social fall – an upheaval that left deep imprints on little Henrik. The characters in his plays often mirror these early painful experiences of his, and his themes often deal with issues of financial difficulty, as well as moral conflicts that come from darker private secrets that are often hidden from society.

Born 1828, in Skien, Southern Norway, Henrik Ibsen was the son of a successful businessman. When he was a boy his family’s fortune took a dramatic turn for the worse. They experienced a severe social fall – an upheaval that left deep imprints on little Henrik. The characters in his plays often mirror these early painful experiences of his, and his themes often deal with issues of financial difficulty, as well as moral conflicts that come from darker private secrets that are often hidden from society.

To ensure his place in higher education, Henrik’sfather arranged for him to work as an apprentice in a pharmacy, in the coastal town of Grimstead. He published his first play aged 22. His success as a playwright, however, was not to come until much later. From 1850 to 1858 he worked as Artistic Director of the first Norwegian Theatre house in Bergen, returning to Oslo only to experience rejection and hardships. Becoming increasingly disillusioned, and at the same time choosing to believe in his own artistic and cultural ideas, he decided to leave Norway for Italy. This initial travel and stay was made possible through friendly benefactors. In Italy, Ibsen wrote his first poetic drama Brand (1865). This vibrant study of religious extremism and moral conflicts earned him European fame, and a substantial grant from the Norwegian Government, which ensured him the possibility of further artistic growth. This gave him the time and space he needed: leading to his masterpiece study of Norwegian ‘folk soul’ – Peer Gynt (1867).

These plays won Ibsen wide artistic as well as critical acclaim. This recognition afforded him the freedom and confidence to dare to express stronger judgements and beliefs that tested social, ethical and personal issues of his time. The body of work he developed during this period, which he termed the “drama of ideas” constituted a profound and rich expression of human fate and destiny. Testament to the power of his descriptions of humanity is that his plays are performed in more than 20 theatres around the world every day.

These plays won Ibsen wide artistic as well as critical acclaim. This recognition afforded him the freedom and confidence to dare to express stronger judgements and beliefs that tested social, ethical and personal issues of his time. The body of work he developed during this period, which he termed the “drama of ideas” constituted a profound and rich expression of human fate and destiny. Testament to the power of his descriptions of humanity is that his plays are performed in more than 20 theatres around the world every day.

These, plus his next series of plays gave him more power, income and influence, as well as placing him at the centre of philosophical, social and political controversy across Europe. His work also became vitally important for the development of our modern understanding of fundamental human rights.

In 1879, A Doll’s House was published. Being a scathing criticism of the traditional roles of men and women in Victorian marriage, the play roused outrage and disgust, as well as consolidating Ibsen’s reputation for fighting the ’cause of humanity.’ “I must decline the honour consciously to have worked for the cause of women. For me it has appeared to be the cause of human beings. . . .My task has been to portray human beings” Henrik Ibsen, 1898

The response to A Doll’s House in Ibsen’s day was divisive, to say the least. People were hurt and provoked. At a particular dinner party in Oslo, a plea was written on the invitation card: ‘we kindly ask our guests to refrain from discussing A Doll’s House.’ So controversial was the play’s ending, that a renowned German actress playing Nora refused to act out leaving her husband and children. Ibsen reluctantly wrote an alternative ending for this one production, where Nora stays, for the sake her children. Critics bemoaned the lack of reconciliation between Nora and her husband. Socialists and radicals, on the other hand, praised the play for condemning everyday life!

The response to A Doll’s House in Ibsen’s day was divisive, to say the least. People were hurt and provoked. At a particular dinner party in Oslo, a plea was written on the invitation card: ‘we kindly ask our guests to refrain from discussing A Doll’s House.’ So controversial was the play’s ending, that a renowned German actress playing Nora refused to act out leaving her husband and children. Ibsen reluctantly wrote an alternative ending for this one production, where Nora stays, for the sake her children. Critics bemoaned the lack of reconciliation between Nora and her husband. Socialists and radicals, on the other hand, praised the play for condemning everyday life!

Ibsen stressed that the director of his plays should endeavour to create, “truth to life: the illusion that everything is real and that one is sitting watching something that is taking place in real life.” With A Doll’s House, Ibsen completely rewrote the rules of drama with a ‘realism’ that radically challenged the social order and moralistic, romantic theatre forms. From Ibsen forward challenging assumptions and directly speaking about issues has been considered one of the factors that makes a play Art, rather than entertainment.

Synopsis

Nora is happily married to Mr. Madalitso Jere. It’s Christmas, and the house is bustling with happiness. Jere is a businessman who has just won the position of Human Resources Manager at The Blantyre Insurance Bank (BIB) Nora is happily married to Mr. Madalitso Jere. Its Christmas, and the house is bustling with happiness. Jere is a businessman who has just won the position of Human Resources Manager at The Blantyre Insurance Bank (BIB).

They have three small children and live in a town house, with an insulated ceiling and a corrugated iron fence, in Chinyonga, a ‘better side’ of town.

Underneath all the action in this play, there are silent cries of:

‘SEE ME!’ ‘SEE WHO I AM!”UNDERSTAND ME!’

‘UNDERSTAND WHAT I WANT & WHAT I NEED!‘

Nora has a secret to keep, however. Early in their marriage, Nora felt she had no choice but to take a certain dubious course of action in order to obtain the means necessary to save her husband’s life. Mr. Jere was suffering from a ‘stress-related heart condition’ and could not be told at the time how dangerously ill he was. Nora considers her act of ‘saving Jere’s life’ to be a great testament of her love for him.

To save her husband’s life, without him knowing Nora enlisted the help of a certain lawyer, Katswiri Chikaona. Her dealings with this man have to remain a secret.

When the play opens, an old friend of Nora’s Mrs Christina Kamwendo arrives in town to look for work, and Nora sees to it that Jere gives her a post at the Blantyre Insurance Bank. Katswiri Chikaona also works at the bank, and Christina’s employment there means that Chikaona is dismissed from his post.

In desperation, Chikaona goes to Nora and threatens to tell Jere about her arrangement with him unless he is allowed to keep his post. Nora is in despair but at the same time has become convinced that in his love for her, Jere will sacrifice himself and take full responsibility for what she has done, if he learns the truth. This is because Jere believes and asserts that he is ‘such a man that can, in the face of floods, take it all on himself.’ Nora however, vows that she would rather kill herself than let her husband go through with such a sacrifice.

Nora considers asking Dr Fundo, an old friend of hers and Jere’s, for help. But, when Dr Fundo declares his true feelings for her, Nora finds it impossible to ask him.

After Chikaona has lost his job at the bank, he writes a letter to Jere revealing what Nora and he did in the past. Contained within this letter is a threat to both Nora and Jere that unless his position at the bank is restored, he will reveal everything to the police. After Jere reads the letter, he reacts with rage and revulsion, refusing to see that Nora acted out of love for him, and without any sign of willingness to accept responsibility for her actions.

Christina, who was in love with Chikaona in the past, gets him to change his mind and withdraw his threats. Mr. Jere is overjoyed.

But Nora has begun to understand that her marriage, her love and her duties in life are not what she thought they were, and in the course of a devastating conversation with Jere she decides that her most important and only task is to go out in to the world on her own, to “bring herself up”.

She leaves her husband and children.

Making Sense of the Past…

In 1997, Jere becomes seriously ill and the doctors tell Nora that his ‘stress related heart condition’ is lethal; it will kill him if he does not seek treatment immediately. The kind of treatment he needs is only available in South Africa. The cost of the trip and treatment is 490,000 Malawi Kwacha. Nora cannot let Jere know how ill he is, so her attempts at persuading him to take the trip are futile, particularly as they don’t have the money needed to go. Nora tries to persuade Jere to ask her father for the money, or to take a loan – Jere is adamant – this is not an option. What a humiliating prospect for this proud man who wishes to stand on his own two feet and be a creator of his own wealth. Under no circumstances would his principals allow him to be beholden to Nora’s father, or to ever become indebted.

In 1997, Jere becomes seriously ill and the doctors tell Nora that his ‘stress related heart condition’ is lethal; it will kill him if he does not seek treatment immediately. The kind of treatment he needs is only available in South Africa. The cost of the trip and treatment is 490,000 Malawi Kwacha. Nora cannot let Jere know how ill he is, so her attempts at persuading him to take the trip are futile, particularly as they don’t have the money needed to go. Nora tries to persuade Jere to ask her father for the money, or to take a loan – Jere is adamant – this is not an option. What a humiliating prospect for this proud man who wishes to stand on his own two feet and be a creator of his own wealth. Under no circumstances would his principals allow him to be beholden to Nora’s father, or to ever become indebted.

With little financial independence, no assets or bank account of her own, Nora has to find another way of getting the money. She approaches Katswiri Chikaona, A lawyer who was involved in setting up her father’s company. Nora’s father has been ill for two years. His company has not been functioning, profits plummeting, debt accumulating. Towards the end of his days he prepares to put his company in ‘trust’ in his will. He will entrust the company to Nora and his younger brother. But Nora does not know this at the time she seeks out money. Chikaona does however, and when Nora contacts him, he can’t believe his luck; he knows he must move fast to exploit the situation to its full money-spinning capacity.

This opportunist, Chikaona, assures Nora that he can arrange for her father’s company to loan her the money. Nora wonders how this can be possible. Chikaona tells her that her father will put the company in trust to her, and her uncle, in his will. But this might not happen in time for Nora to get money out of the company to save her husband – Chikaona makes this clear.

Chikaona says he can arrange a loan for her through the company, and in addition he has a clever proposal, that he says will be of mutual benefit to them both. Firstly, in order for Chikaona to arrange the loan, Nora’s father needs to sign a ‘surety’ – thus guaranteeing a bank loan against his property, and the remaining company assets. This would allow the bank to loan the company the necessary amount to: make funds available to solve Nora’s problem, and allow the company to get back on its feet. Secondly, Nora must persuade her father to sign over ‘power of attorney’ to Chikaona. This means, first of all, that when the company is entrusted to Nora and her uncle, he will be able to facilitate a low interest loan repayment, and second of all he pledges to re-build the company on her behalf. He assures her this is necessary if she doesn’t want to be pushed out by her uncle. So long as he, Chikaona himself, has ‘power of attorney’, her interests in the company will be protected.

When Nora goes to her father with Chikaona’s documents to sign, he is slipping in and out of consciousness. He understands that Nora is in need of help; he agrees that Nora should do what ever she thinks is the right. He is unable to sign the papers, he cannot even grip the pen. Nora forges her dying father’s signatures on the two documents. The document handing power of attorney to Chikaona, and the document proving ‘surety’ for the company loan. Both documents she puts her signature as witness.

In another secret meeting with Chikaona, she brings him the signed papers. He forces himself upon her – trying to win some sexual favours. Disgusted, Nora considers for a moment forgetting the whole deal. But the clock is ticking and she sees no other way of getting the money to save Jere.

Having secured the money, Nora lies to Jere – telling him that her father has offered her a loan. She reasons with him – that considering how he helped her father in 1994, this loan is simply a way of returning a favour; it is a way of Nora’s father repaying his dues to Jere. Jere agrees. Shortly after everything is arranged, Nora’s father passes away. The trip to South Africa saves Jere’s life. He has not been ill a day since. Nora’s hopes for paying her loan off through money earned by the company are hopeless. The company’s profits never reach her pockets. The company used to manufacture and supply textbooks and educational materials for schools.

For the first few years after Nora’s father passes away, the company becomes increasingly successful, operating with wider range of goods and services, including procurement of ARVs for district hospitals and health centres. Procuring, importing and distributing treadle pumps, condoms, fertilizer, maize, anti-malarial drugs, material for government and public service uniforms, even land rovers. In short, the company becomes an instrument for bribery, corruption and money laundering.

From 1997 to the present day, Nora is indebted to the company. Chikaona makes a killing through the company’s operations. Between 1997 and 2000, the company thrives, through all sorts of clandestine deals, tenders, imports and exports. What this means for Nora is that her repayments are smaller, because her small share in the company generates little profit. But Chikaona becomes increasingly cavalier in his deals and tenders on behalf of the company. In 2000 there are whisperings that the Public Accounts Committee in parliament are about to conduct investigations in to the company’s operations. Chikaona uses his influence to avert attention from the company, protecting Nora from possible legal cases against her.

The rumour and suspicion around the company’s activities mean it is harder for Chikaona to cut deals. He becomes increasingly alienated by both the company’s ‘official’ and ‘unofficial’ partners. The profits earned are squandered, and the company becomes worthless. The uncle is only active in the company’s activities for a few years after Nora’s Father’s death. He then becomes ill himself and has very little to do with Chikaona’s deals etc. Ever since Nora has had to scramble for money to pay back the loan to the company through Chikaona – using her housekeeping allowance and extra money from some small odd jobs.

The Meaning of the Play in Malawi…

Women in Malawi experience a general subordinate status, and have limited access to the law and productive resources such as land, technology, credit, education, training, and formal employment. Gender-based inequalities directly and indirectly limit economic growth and diminish the effectiveness of poverty reduction efforts, they also make life in general much more painful and strenuous than is right and acceptable, for women across the country. The gender disparities that manifest themselves in all areas including the social, economic, political and cultural spheres throughout the ‘public’ domain, certainly stem from the ‘private’ world in the home.

Despite the notable steps forward in the area of , ‘Gender development’ is a relatively new priority for development discourses and activity in Malawi. Breaking the Pot is being dramatised here at a crucial time for women’s rights: long awaited and crucial legislation, the Domestic Violence Bill and the Wills and Inheritance Act, is soon to be tabled in parliament; the media has recently been awash with the most vicious images and brutal stories of violence against women: their arms chopped off, their faces burnt, their eyes gouged out. It is clear that many changes must take place before women will be relieved of the fear caused by entrenched and oppressive cultural norms and values.

This production certainly hopes to provide much food for discussion and thought around the relationships people live out in marriage here in Malawi.

Questions to consider:

• What would have to been different in order for the play to have a different ending?

• Do you judge Nora?

• How do you judge Mr Jere?

• What made you angry in the story?

• How do men relate to their sense of masculinity?

• Do men really want their women to feel subordinate to them?

• Is it possible to be really honest and truthful in a relationship?

• What do we hide from our closest partner?

• How do we theatricalise ourselves, play out ‘roles’ in our own lives?

• What would we ‘sacrifice’ for love?

• What do we understand love to be?

• How can men and women better understand one another?

• What fantasies do we have in relation to our husband or wives?

• What does it mean to be masculine?

• What does it mean to be feminine?

• Do we feel respected, as human beings?

• Do we really show ‘respect’ in ourrelationships?

• Do we really feel understood, by thoseclosest to us?

• Are we prepared to change?

Post-show discussion:

“This play that calls for a radical transformation not just, or not even primarily, of laws and institutions, but of human beings and their ideas of love.” Toril Moi “First and Foremost a Human Being”:

Idealism, Theater and Gender in A Doll’s House, 2006

Dramatising…

The detailed work with the actors has been based upon activating the ‘inner life’ of these characters: focusing on unearthing the ‘sub-text’ beneath the words themselves

- always asking, what is really going on here? What are these people really doing? What does Nora really mean and want when she shows Jere the nice and cheap things she has bought for Christmas? The representation you will experience today is the result of a long rehearsal process of many exercises and discussions that have intended to pinpoint the precise and essential action under the text.

The detailed work with the actors has been based upon activating the ‘inner life’ of these characters: focusing on unearthing the ‘sub-text’ beneath the words themselves

- always asking, what is really going on here? What are these people really doing? What does Nora really mean and want when she shows Jere the nice and cheap things she has bought for Christmas? The representation you will experience today is the result of a long rehearsal process of many exercises and discussions that have intended to pinpoint the precise and essential action under the text.

In order to emphasise the role that society and the past play in the Jere’s lives, we have placed the sitting-room, and indeed the story within a space, intended to represent ‘the context’. The chorus, who perform an originally composed soundtrack and provide an additional emotional underscore, also represent the context in which this marriage takes place. They express the social and cultural pressures placed upon both men and women to live out their lives according to rigid roles, and oppressive power structures. They also express moments from the past in order to take care of Nora’s full story.

Common responses to Nora, in Malawi, as we have developed the text:

• She is a manipulator.

• She is not obedient.

• Jere forgave her, she should have stayed!

Cast

- Mbumba Mbewe

- Mafumu Matiki

- Henry Mtalika

- Susan Chowe

- Sam Kuseka

- Watupa Mtambo

- Lynet Kunkeyani

- Esther Kaunda

- Bennie Msuku

- Mariam Shaibu Itimu

- Noah Bulambo

- Chimwemwe Maloya

- Fred Muphuwa

Crew

- Movement specialist, Choreographer: Sam Moss

- Production Artist: Lovemore Khankwani

- Stage and production manager: Jafali Amadu

- Stage and production manager: Hussein Gopole

- Graphic Designer: Julie Hankins

- Co-writer for this adaptation: Karl Hoff

- Assistant Director, playwright: Thoko Kapiri

- Co-writer of first draft: Alfred Msadala

- Producer: Basimenye Mwalwanda

- Executive Producer, Playwright, Director, Facilitator, Actor: Muthi Nhlema

- Director, co-writer, producer Co-founder and Creative Director of Nanzikambe: Melissa Eveleigh

Stunning… beautifully directed..